Simple vanilla restaurant booking system

Combining NpgsqlRest and vanilla SQL, HTML, JS and CSS

In this post, I’ll tell you a bit about what NpgsqlRest is like to use, and whether it lives up to the claims I made in the last post. I picked the restaurant booking system as it is complex enough to give me a good idea of what the stack can do, and it includes enough variety in the kind of challenges that one might run into while building an app out in the wild.

If you’re in a hurry, you’ll find the source code here.

The app is called MyTable—a nod to the era when every tutorial started with “my” something, “table” doing the double-duty of referring to both database tables and restaurant tables.

In this post, I’m not covering the frontend parts. I’m mostly focusing on the NpgsqlRest itself and what writing SQL backends looks like. I’ll cover frontend in a future post.

About the use of AI

Let me first get this out of the way.

I used AI for developing this app, just like I normally do for work. Some of my readers may find this surprising given that I don’t use libraries—most of the time anyway—but I’m really not anti-AI or anything like that. I’m anti-bloat, and anti-complexity, but AI doesn’t add complexity or bloat to my work or its output, so I’m ok with it.

If you’re using AI for development, then you should really consider going vanilla. It’s going to make your app faster and slimmer, simplify (or even eliminate) your build pipeline, and dramatically reduce the amount of moving parts end-to-end. What’s not to like?

Development environment

I’ve set up a development environment within a Lima VM. This is a standard practice I employ with all clients as it allows me to separate out the different dependencies, system packages, and other things the projects may need. However, with DCA (database-centric architecture) and vanilla frontend, I think this setup may be a bit too heavy-handed. I could see myself just using Docker Compose or something along those lines.

The environment includes:

Ubuntu LTS—this is the base VM image

Postgres 18—the latest version of Postgres

dbmate—simple tool for schema migrations

NpgsqlRest—the thing I want to check out 😉

ab—for rate limiter testing

These are all binaries without tens of thousands of dependency packages. For some people it may sound pretty normal, but if you’re coming from the JavaScript ecosystem then you know what I mean. I like these frugal development experiences, if I’m being honest.

As usual, I set up the environment using a shell script. I write it—well, generate it—so that it’s idempotent, and when I need to change something about the environment, I just modify the script.

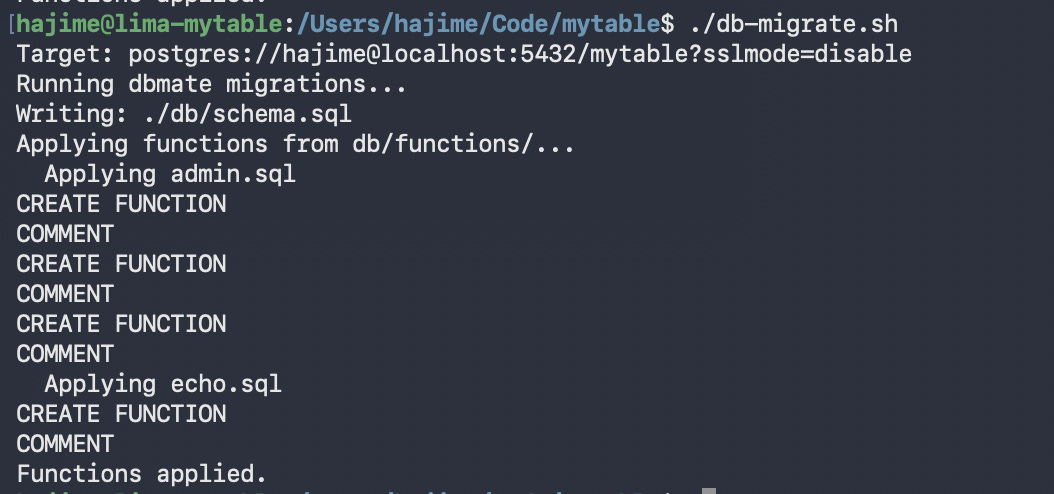

Database migrations

The database migrations are done using two different tools. I use dbmate for schema migrations stored in db/migrations with the traditional up/down pairs. The stored functions are updated using idempotent SQL statements in db/functions, which are simply run using psql. This is because functions can be dropped and replaced at will without losing data—I don’t need to explicitly version them or something.

I created a simple shell script to automate this. For now it will be sufficient. If I end up needing more sophistication, there’s a tool called pgmigrations written by Vedran Bilopavlović, NpgsqlRest’s author.

The tests for the functions are written in the same SQL file as the functions themselves. They are written in a transaction so that they can be run as part of the migration.

begin;

do $$

declare

v_setup boolean;

v_auth boolean;

v_login record;

begin

truncate admin_users restart identity cascade;

-- is_setup returns false when no admin

select setup into v_setup from is_setup();

assert v_setup = false, 'setup should be false when no admin exists';

-- is_setup returns true when admin exists

insert into admin_users (username, password_hash) values ('admin', 'hash');

select setup into v_setup from is_setup();

assert v_setup = true, 'setup should be true when admin exists';

-- ......

raise notice 'All admin tests passed!';

end;

$$;

rollback;I didn’t go as far as to perform a full rollback of the entire migration when one test fails, tho. To me it’s good enough to do a quick cortisol-driven fix on failure in this particular case. With databases, the likelihood that something that passes locally will fail on the production server are fairly minimal.

Middleware configuration

I configured NpgsqlRest with two configuration files. The base default.json, and a local configuration file local.json that includes environment-specific settings. The configuration includes the ability to serve static files from the public folder, where I’m going to keep my frontend assets. The local configuration is not checked into version control.

When starting, I start with:

NpgsqlRest default.json -o local.jsonI find the configuration system delightful. If you specify a file using -o, the file becomes optional, and its absence is silently ignored. Neat!

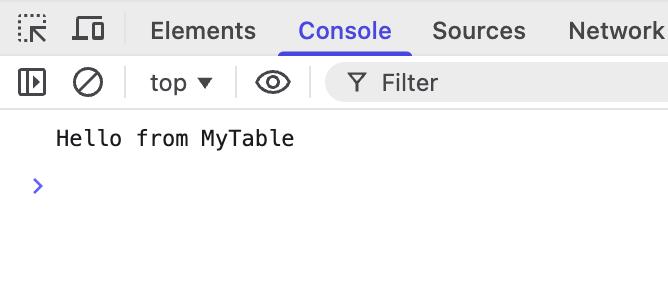

Initial test

The first step is to test the setup. I create a small test function.

create or replace function echo(message text) returns text as $$

select message;

$$ language sql;

comment on function echo(text) is 'HTTP

Echoes the input message back';This is then wired up in the frontend:

fetch('/api/echo', {

method: 'POST',

headers: {'Content-Type': 'applicaiton/json'},

body: JSON.stringify({message: 'Hello from MyTable'}),

})

.then(res => res.text())

.then(console.log)

.catch(console.error)Good to go:

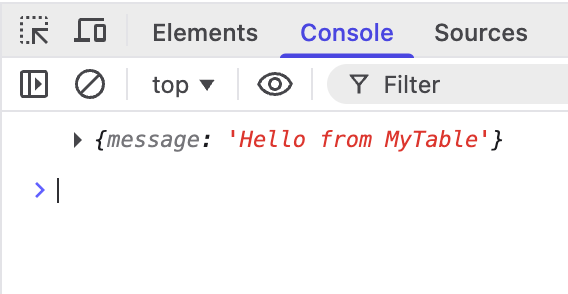

Hot reloading

Hot-reloading with NpglsqlRest works only when you’re changing the implementation of the function.

If, like in the following example, I change anything about the function metadata (return type, annotations, etc.) I need to restart the server. This is generally doesn’t take a lot of time, so it’s not a big issue.

drop function echo(text);

create function echo(message text) returns jsonb as $$

select jsonb_build_object('message', message);

$$ language sql;

comment on function echo(text) is 'HTTP

Echoes the input message back';And to update the client-side code:

fetch('/api/echo', {

method: 'POST',

headers: {'Content-Type': 'applicaiton/json'},

body: JSON.stringify({message: 'Hello from MyTable'}),

})

.then(res => res.json())

.then(console.log)

.catch(console.error)When the middleware is restarted, we get the new results:

Hopefully, new versions will be able to pick up on these (e.g., maybe a background job that periodically flushes the definitions). Vedran tells me it’s because of the rate limiter implementation which was not compatible with hot-reloading.

Automatic JSON serialization

NpgsqlRest supports automatic JSON serialization of tables and even single-object returns using composite types.

I normally do JSON serialization in the database itself. The difference between doing it in the DB vs doing it in the middleware is, performance-wise, probably negligible. However, doing it in the middleware separates the concerns and frees you from having to worry about it… mostly.

AI picked it up from the NpgsqlRest docs, and generates code using custom types regardless of what I thought about it, however.

-- Composite type for reservation summary in table status

drop type if exists reservation_summary cascade;

create type reservation_summary as (

id int,

guest_name text,

party_size int,

reservation_time time,

duration_minutes int,

status text

);

-- Get table status for a specific date (includes reservations and block status)

-- Block duration: 30 min base + 30 min per seat

drop function if exists get_table_status_for_date(date);

create function get_table_status_for_date(p_date date)

returns table(

id int,

floorplan_id int,

name text,

capacity int,

x_pct numeric,

y_pct numeric,

is_blocked boolean,

block_notes text,

block_ends_at timestamptz,

reservations reservation_summary[]

) as $$

-- ....

$$ language sql;Note that there are some APIs that require tables to be returned (e.g., endpoints marked with @login). The overall feel is that NpgsqlRest prefers tables and is built around the idea of using tables. You will probably take better advantage of this tool if you stick to tables.

I’ve converted all my functions to use tables to see what it’s like. I notice that AI is more comfortable using manual JSON serialization than custom types and tables. It requires a bit of hand-holding and custom rules to get in the groove.

Site setup and authentication

This is a single-tenant app. This means that it’s deployed separately for each owner. Because of that, it behaves more like a WordPress or CMS deployment where the first time you deploy, it greets you with a setup page.

The user table is simple:

-- migrate:up

create extension if not exists pgcrypto;

create table admin_users (

id serial primary key,

username text not null unique,

password_hash text not null,

created_at timestamptz not null default now()

);

-- migrate:down

drop table if exists admin_users;This is not intended for a consumer and I assume either direct administrative privileges or access to support, I’m not spending time on fluff. No email actions, no password reset, etc., no tracking of last login, account activation, etc.

I could have used HTTP basic auth, too, but wanted to see how the regular user account authentication works with NpgsqlRest.

Cookie authentication is handled by marking the login endpoint with a @login annotation, and the protected endpoints with @authorize.

The @login annotation can be used to offload password hash checking to the middleware, too, but that requires the hash algorithm to be specifically PBKDF2-SHA256. Since I prefer to go with built-in stuff when they’re available, I went with the bog-standard bcrypt and forego hash checking inside the middleware. This should generally be fine unless there’s compliance shenanigans involved.

The login function looks like this:

-- Admin login

create or replace function admin_login(

username text,

password text

) returns table(status boolean, user_id int, user_name text) as $$

select true, a.id, a.username

from admin_users a

where a.username = admin_login.username

and a.password_hash = crypt(admin_login.password, a.password_hash);

$$ language sql;

comment on function admin_login(text, text) is 'HTTP POST

@login

Authenticate admin user';The status column returned by this function is part of the @login contract, and tells NpgsqlRest whether the login was successful or not. The other two columns are returned as part of the payload.

Any columns returned by the login endpoint are treated as claims, too. This can be used to authorized based on specific claims. These claims can then be mapped to function parameters in the configuration. I haven’t used these features in this test, but it’s very comprehensive, and it seems like it would cover most authorization scenarios I can think of.

Additionally, there’s a function to check if the site is set up:

-- Check if system is set up (has at least one admin)

create or replace function is_setup() returns boolean as $$

select exists(select 1 from admin_users);

$$ language sql;

comment on function is_setup() is 'HTTP GET

Check if the system has been set up with an admin account';And a function to set it up:

-- Setup first admin account (only works when no admins exist)

create or replace function setup_admin(

username text,

password text

) returns void as $$

begin

if exists(select 1 from admin_users) then

raise exception 'System is already set up';

end if;

insert into admin_users (username, password_hash)

values (setup_admin.username, crypt(setup_admin.password, gen_salt('bf')));

end;

$$ language plpgsql;This function specifically prevents multiple setup attempts. If and when I get around to staff management, I’ll add a separate endpoint for that. I like to keep separate endpoints for things that may evolve separately.

And last but not least, I have an endpoint that checks authorization. This is a dummy endpoint that doesn’t touch the database. It’s there specifically to trigger NpgsqlRest’s authorization mechanism:

-- Check if current session is authenticated

create or replace function is_authenticated() returns boolean as $$

select true;

$$ language sql;

comment on function is_authenticated() is 'HTTP GET

@authorize

Returns true if authenticated, 401 if not';The @authorize annotation is doing all the heavy-lifting here. The function is not even called if the user is not authorized.

On the client side, I have guards for each condition. The guards are small scripts that are executed while the page is parsing. They load fast, fire a request to check for issues, and redirect to a page designed to resolve the issue. We’re talking 100~400 bytes a pop without minification.

The back-office page page is guarded like so:

let go = url => location.replace(url)

fetch('/api/is-setup')

.then(r => r.text())

.then(v => {

if (v != 't') go('setup.html')

return fetch('/api/is-authenticated')

})

.then(r => {

if (r && !r.ok) go('login.html')

return fetch('/api/is-restaurant-configured')

})

.then(r => r?.text())

.then(v => {

if (v == 'f') go('restaurant-setup.html')

}) This is 360 bytes checking for completion of initial setup, authorization, and restaurant setup, diverting the user to appropriate setup pages.

To load these checks I use:

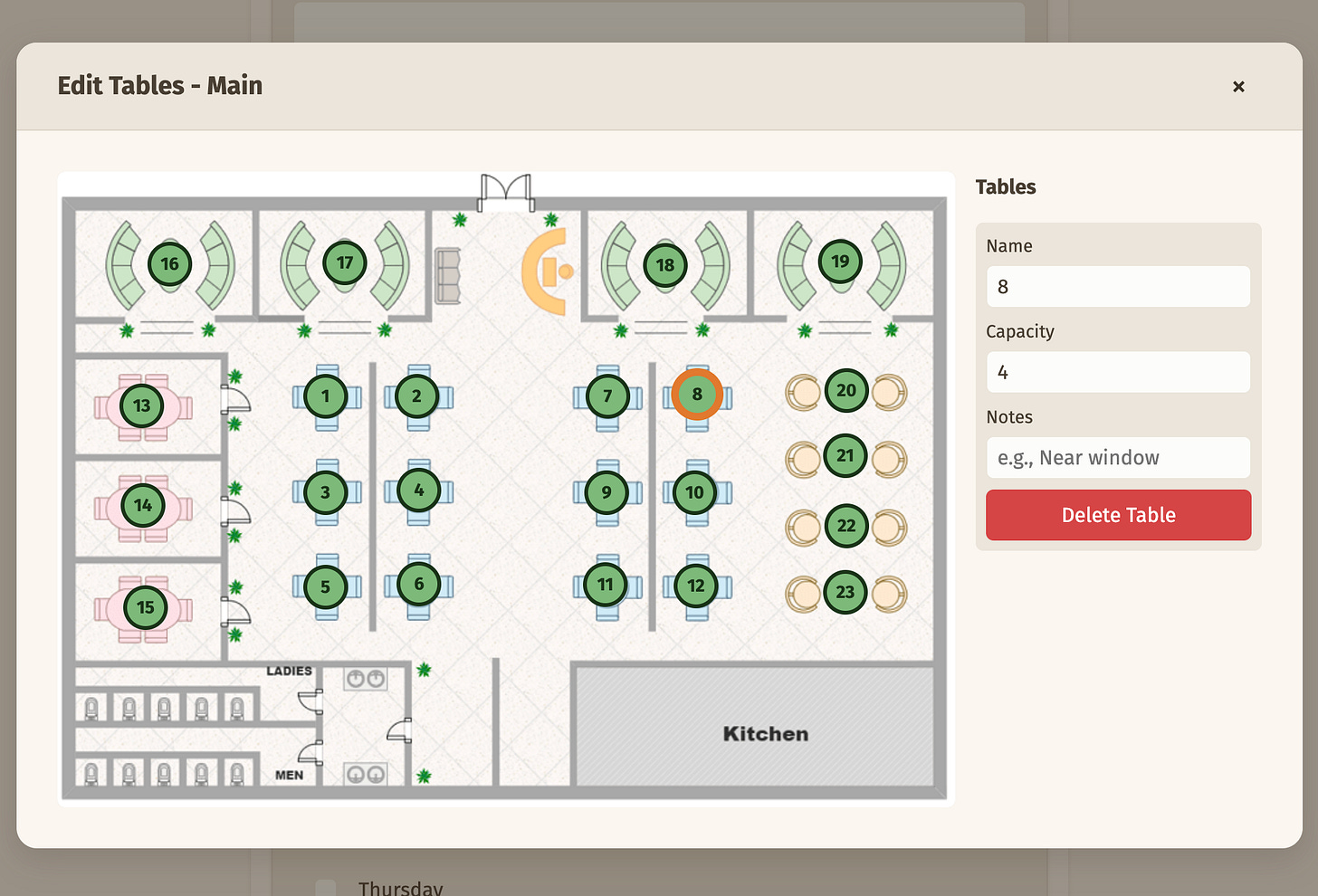

<script async src="backoffice-check.js"></script>The restaurant setup

The administrator has to specify some information that are relevant to the customer wanting to book a table as well as the information they need to confirm it. This includes the work hours, table layout, basic contact information, and so on.

The workflow is this: the admin enters the details, upload floor plans, and then sets up the table layout by marking areas on the floor plan.

The system is always used by a single restaurant. To store the restaurant configuration, I use a singleton table pattern. The restaurant (singular) table has the following column:

id int primary key default 1 check (id = 1) It’s not auto-incrementing and it has a check clause that ensures the id column is always 1. If the setup code runs twice for some odd reason, the database won’t end up with two records.

The floor plan upload is handled by NpgsqlRest. As you might have guessed, it’s handled by a stored function which looks like this:

create or replace function upload_floorplan_image(_meta json default null) returns json as $$

begin

return json_build_object(

'success', true,

'path', '/' || substr(_meta->0->>'filePath', 8)

);

end;

$$ language plpgsql;

comment on function upload_floorplan_image(json) is 'HTTP POST

@authorize

@upload for file_system

Upload floorplan image file';The @upload for file_system annotation works in tandem with the configuration, and dumps the files to public/upload/*.*. The uploaded file metadata is passed the the function as a _meta argument, and then the endpoint can convert that into a response. A separate endpoint is used to save the other data:

create or replace function save_floorplan(

p_name text,

p_image_path text,

p_image_width int,

p_image_height int,

p_sort_order int default 0

) returns int as $$

insert into floorplan (name, image_path, image_width, image_height, sort_order)

values (p_name, p_image_path, p_image_width, p_image_height, p_sort_order)

returning id;

$$ language sql;

comment on function save_floorplan(text, text, int, int, int) is 'HTTP POST

@authorize

Save a new floorplan';The image height and width are calculated client-side using the naturalWidth and naturalHeight properties on an img object:

let getImageDimensions = (file) => new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

let img = new Image()

let url = URL.createObjectURL(file)

img.onload = () => {

URL.revokeObjectURL(url)

resolve({

width: img.naturalWidth,

height: img.naturalHeight,

})

}

img.onerror = () => {

URL.revokeObjectURL(url)

reject(new Error('Failed to load image'))

}

img.src = url

}) The rest of it was pretty much uneventful. NpgsqlRest generally stays in the background and lets me focus on fairly standard SQL and the frontend code.

Real-time notifications

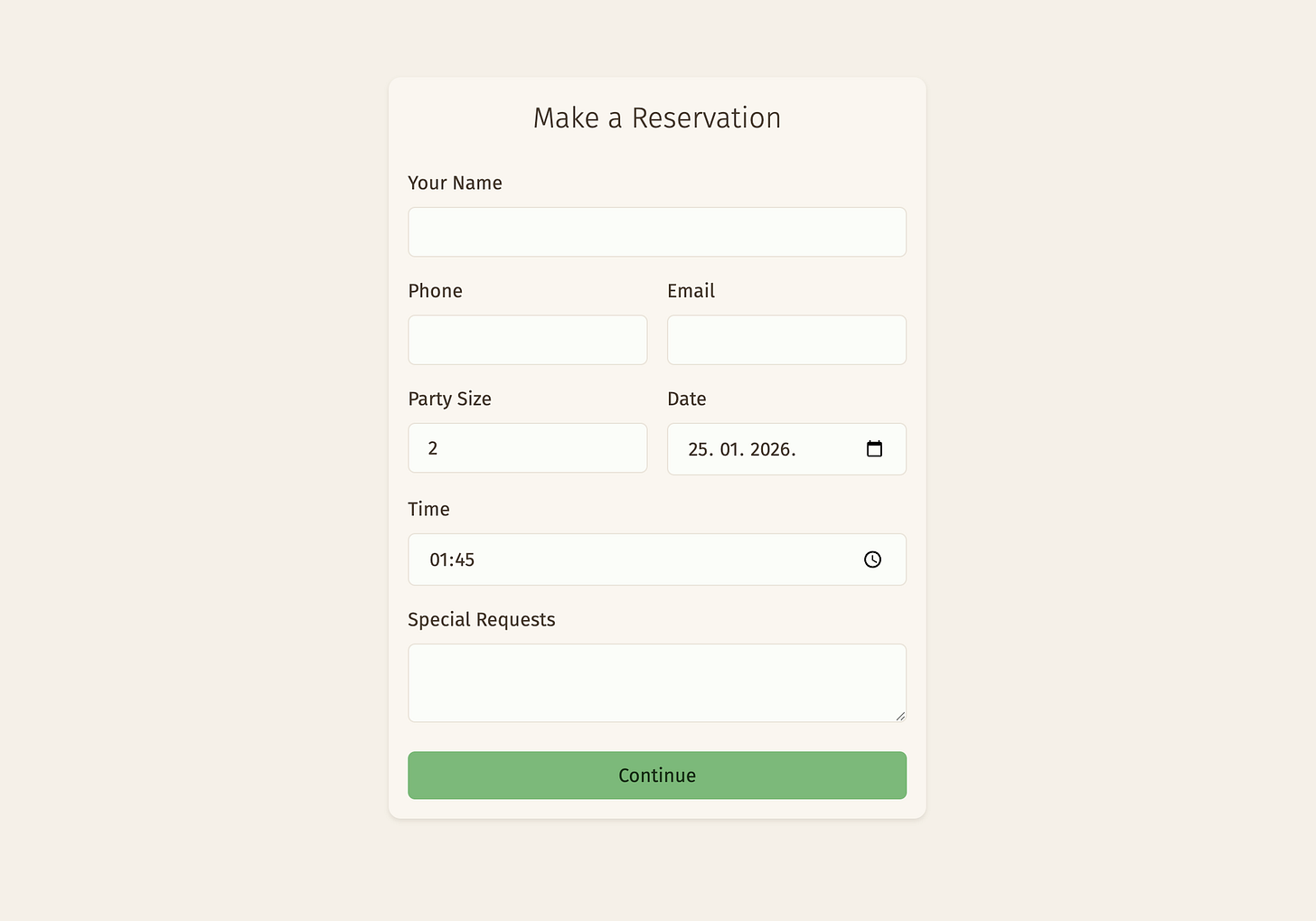

Once the restaurant is set up, the administrator can start taking reservations. There are a few ways to take reservations. Walk-in, by phone, and through the customer-facing online interface.

Walk-in and phone reservations are handled solely by the administrator punching in all the details. Typical CRUD operation, no fanfares. Just her, the computer, and the forms. This is handled in the backend with a simple function that inserts the information.

The real interesting stuff happens when we have reservations from the customer-facing page.

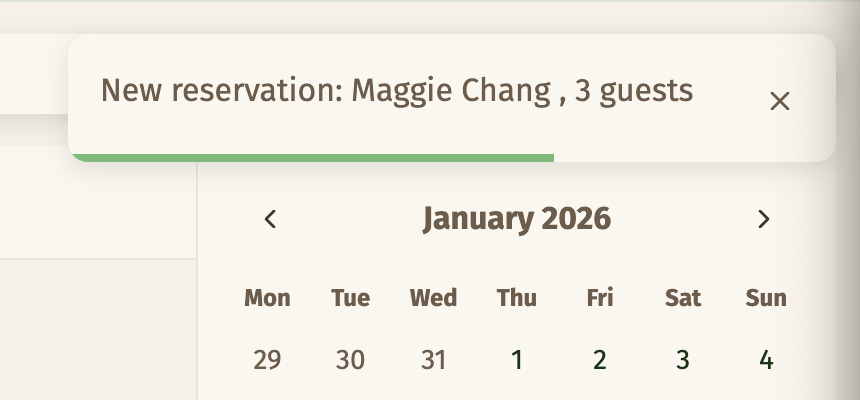

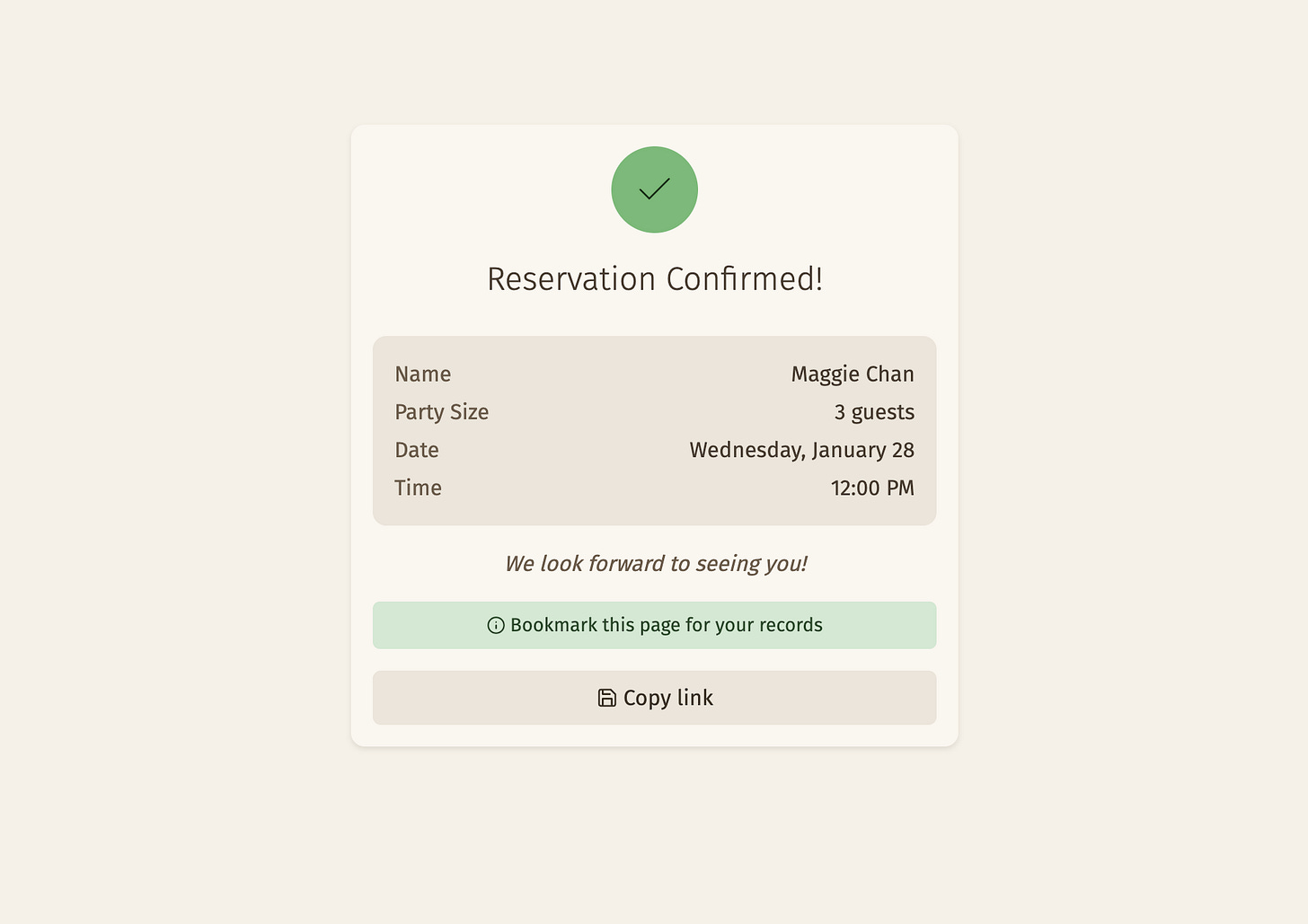

When a customer submits the form, they are subscribed to a feed that will give them the real-time notification when the staff reviews and accepts or declines it. Meanwhile, the staff is subscribed to a feed that gives them new reservation notifications as they come in.

These features are implemented using SSE (Server-Sent Events). After banging my head around how this is supposed to work in NpgsqlRest, and then reminded by Vedran that there are examples, and having understood how it actually works, I must say I’m a big fan. The implementation is quite elegant.

Let me show you what the reservation resolution endpoint looks like and then I’ll explain how the SSE bit works.

create function resolve_reservation(

p_id int,

p_status text,

p_admin_message text default null,

p_table_ids int[] default null

) returns jsonb as $$

declare

v_token text;

v_code text;

begin

v_code := 'reservation_' || p_status;

-- Update reservation status

update reservation

set status = p_status

where id = p_id;

-- Assign tables if provided

if p_table_ids is not null and array_length(p_table_ids, 1) > 0 then

delete from reservation_table where reservation_id = p_id;

insert into reservation_table (reservation_id, floorplan_table_id)

select p_id, unnest(p_table_ids);

end if;

-- Create notification record

insert into reservation_notification (reservation_id, code, admin_message)

values (p_id, v_code, p_admin_message);

-- Broadcast to SSE clients

select channel_id into v_token

from customer_session

where reservation_id = p_id and expires_at > now()

and channel_id is not null

limit 1;

if v_token is not null then

raise info '%', jsonb_build_object(

'code', v_code,

'channelId', v_token,

'adminMessage', p_admin_message

);

end if;

return '{}'::jsonb;

end;

$$ language plpgsql;

comment on function resolve_reservation(int, text, text, int[]) is 'HTTP POST

@authorize

@sse

Resolve a reservation (confirm or decline) and notify customer';The code is written using PL/PgSQL, a Postgres-specific dialect of procedural SQL. Let me give you a quick overview of what it does.

The reservation is being updated (confirmed/declined)—there’s already an existing reservation.

The tables are assigned by the staff, not the customer, so that needs to be added to the reservation.

A notification record is stored on the reservation page in case the user doesn’t wait for the real-time one and just closes the window. The notification entry is read later when the page is reopened.

A notification message (as JSON) is dispatched via SSE.

The last bit deserves special attention as that’s the core of how SSE works in NpgsqlRest. The function has a @sse annotation, which tells NpgsqlRest to expose an SSE endpoint. This endpoint gets exposed, by default, at /api/resolve-reservation/info, where info is the message level. (You can use other levels, or restrict the level which gets exposed.)

The @authorize annotation on the endpoint refers to the /api/resolve-reservation endpoint itself. The SSE endpoint is public, so that it can be subscribed by the customer.

You have probably noticed that there’s no mechanism for associating the endpoint with specific users. You can’t create dynamic endpoints, etc. The solution to this is to:

not use response data that can identify the specific customer (just saying whether reservation was confirmed or not doesn’t reveal the customer ID)

use a completely random key so that each customer can determine whether the message is addressed to them or not

The channelId is a parameter that gets sent by the customer to be used as the key. It’s UUID v4, and it’s stored in sessionStorage. It is repeated in the SSE payload so that the customer can identify the message as being addressed to them.

Rate limiting

The customer-facing page is designed to be as frictionless as possible. I opted to have no user accounts and use bookmarkable URLs instead. This also means that anyone can spam requests at these URLs, which is not great.

NpgsqlRest has a built-in rate limiter that I can use to plug this hole. The configuration looks like this:

{

"RateLimiterOptions": {

"Enabled": true,

"StatusCode": 429,

"StatusMessage": "Too many requests. Please try again later.",

"DefaultPolicy": "standard",

"Policies": [

{

"Type": "FixedWindow",

"Enabled": true,

"Name": "standard",

"PermitLimit": 60,

"WindowSeconds": 60,

"QueueLimit": 0,

"AutoReplenishment": true

},

{

"Type": "FixedWindow",

"Enabled": true,

"Name": "auth",

"PermitLimit": 10,

"WindowSeconds": 60,

"QueueLimit": 0,

"AutoReplenishment": true

}

]

},

.....

}The rate limiter is uses two profiles. One of these is the default, as specified by the "DefaultPolicy" key. It is used on all endpoints by default.

The "auth" policy is used for authentication endpoints to fend off brute-force attempts. To override the default policy, I use the @rate_limiter_policy annotation:

drop function if exists admin_login(text, text);

create function admin_login(

p_username text,

p_password text

) returns table(user_id int, user_name text) as $$

select a.id, a.username

from admin_users a

where a.username = p_username

and a.password_hash = crypt(

p_password,

a.password_hash

);

$$ language sql;

comment on function admin_login(text, text) is 'HTTP POST

@login

@rate_limiter_policy auth

Authenticate admin user';That’s it.

Conclusion

For those of us who use the database-centric architecture for the backend, NpgsqlRest is a fantastic tool.

Straight out of the box, it gives me everything I need to get started save for a few minor tidbits, for which there are already good solutions anyway.

It really does live up to the promise of fully automatic REST endpoints from the database. After a bit of configuration, you can basically focus on writing the SQL code. It certainly handles everything I need for a backend, and it comes with a ridiculous amount of features to handle anything I might need in the future.

In terms of AI-friendliness, I think it’s reasonably so, though I did find a few cases where it was a bit difficult for AI—or even for me—to figure out how something worked. I think this is just a matter of the project still being young. AI generally handles SQL better than most other languages, so I’m expecting this to become foolproof over time.

Vedran asked me to give him a list of things I’d love to see in future releases, and really I don’t have one. If I had to nitpick, it’d be the ability to truly hot-reload everything while keeping rate-limiting. Otherwise, it’s a compelling package that leaves very little to be desired.

Photo credit: Basile Morin